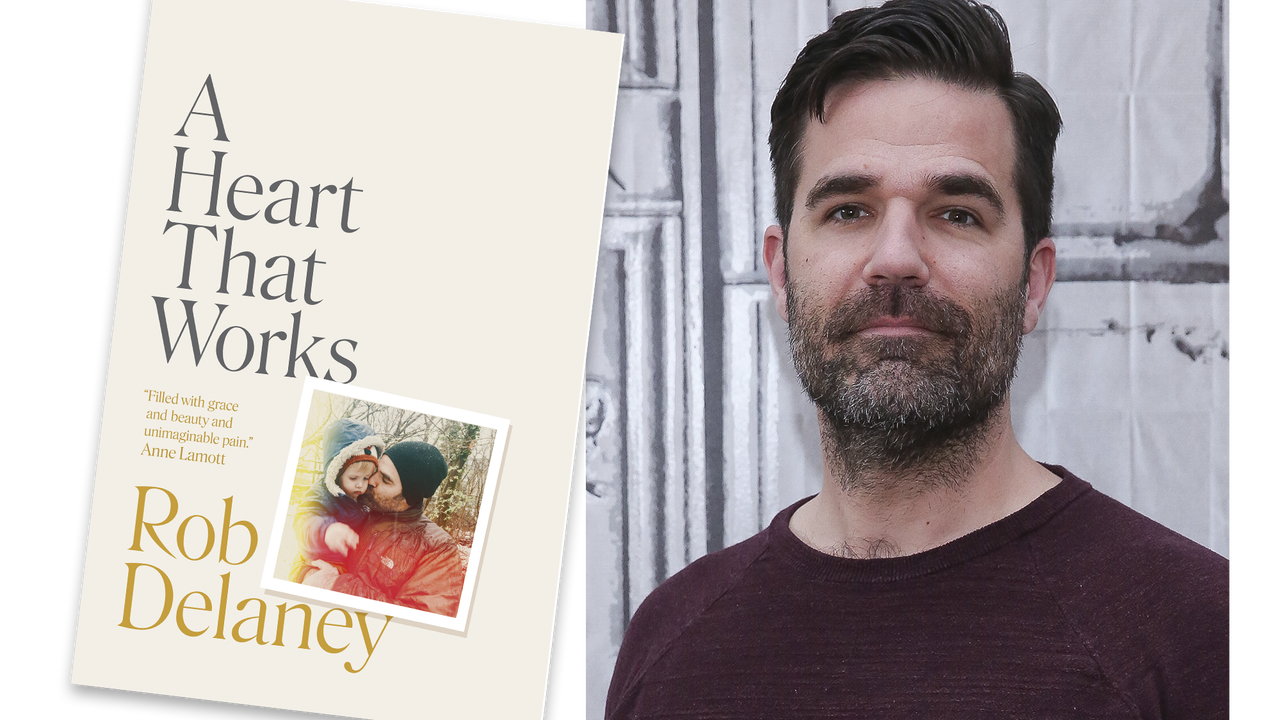

Late last month, Rob Delaney traveled to New York for the US release date of his new book, A Heart That Works, and when he arrived, he asked his 1.5 million followers on Twitter if they knew about any places where he could swim in cold water. In 2012, Delaney received a Comedy Central award for being the funniest person on Twitter, and his surreal and bawdy posts catapulted him into the national eye. Since then, his accolades have far overtaken his tweets—he won a TV Craft BAFTA for Catastrophe, his sitcom with Sharon Horgan, for example—but he’s still a constant presence on the platform.

When we meet for lunch near Madison Square Park that afternoon, Delaney says that his followers suggested plenty of warm places to swim, but nowhere on the open water. He wound up going on a run instead. Despite his affection for Twitter, he isn’t happy about Elon Musk’s ownership. “It’s bad that he owns it,” he says over a turkey club. “It’s definitely him as a person, but also one person shouldn’t be able to just control something important through proclamations.… I really don’t understand the people who go online and are like, Oh yeah, I go to this site just to support the billionaire.”

In person, Delaney is a bit more soft-spoken than you might expect from someone who is so energetic onstage. He explains that though he used to live in New York, he needed help finding a swimming spot because his enthusiasm for the activity in cold water is new. In the opening pages of A Heart That Works, he describes how he started to embrace the discomfort after his two-year-old son, Henry, died of brain cancer in 2018. Henry’s illness and death are the central subjects of the memoir, and Delaney writes about them with bruising intensity and wisdom; he revels in the fact that it is a difficult read. In October, he retweeted a picture of the book’s UK version next to a box of tissues, adding the comment, “Please don’t jerk off to my book.”

Though it is the downer that Delaney was shooting for, there are plenty of moments of pure joy distilled into his descriptions of Henry, like the songs he loved to dance to and his expressive smile. “I have a video of him on the stairs, and he was dancing his way up them and shaking his bum,” he says, noting that he values the experience of being served those moments randomly on his iPhone. “I think it could be healthy for people who are struggling after losing a loved one, to get a little jolt of their memory.”

Now Delaney and his wife, Leah, live in London with their three sons, the youngest of whom was born after Henry died. Henry spent months of his life living in a few different London hospitals, and the book is full of appreciation for the UK’s National Health Service and children’s hospice charities like the Rainbow Trust. In the wake of Henry’s death, Delaney has become an outspoken campaigner on behalf of the organizations that supported his family, speaking at political rallies and even weaving some lewd jokes about his love for the NHS into his stand-up routines.

“Living in the UK when Henry was sick was great because we did not spend time on the phone with insurance, and that would not be the case in the US. So we were very lucky,” he says. But there’s also a more serious purpose to embracing it as a political cause. Privatization and cuts have meant that the system is inching closer to the one in the US. “A lot of people in the UK don’t know what it’s like in the US.”

Delaney is from a small town outside of Boston, while his wife is originally from North Carolina; the family only moved to the UK for Delaney’s work on Catastrophe, which ran for four seasons. They hadn’t necessarily planned on staying long term. “It’s weird, because people ask, ‘Oh, you moved to the UK and fell in love with it?’ We were there and it was absolutely fine, and there were many things we adored about it. We were gonna move back, but then Henry got sick, so we couldn’t,” he says. “And for my older kids, this is home. So now it’s been eight years, and now my oldest just transitioned into secondary school.”

Delaney says that he wanted to write a book about the experience because talking about the kind of grief you feel when you lose a child can be taboo, and the pandemic made it feel all the more urgent. Once he started writing in February, the words came quickly. “Part of the reason why I wrote this book so fast has to do with the fact that if there’s anything you can do to help people through grief now, there’s a hunger for that,” he explains. “With the book, I wanted to write something for people who have gone through the same thing. And I guess in a way I felt this responsibility because I’m a public figure who went through this learning experience.”